Uncovering a piece of history

Rock wall holds names of those who dug tunnels

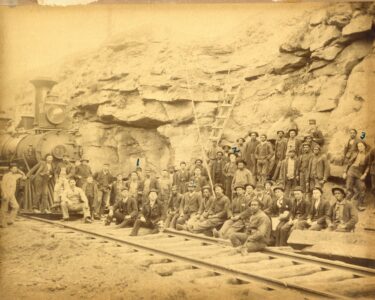

- TAKING A BREAK — Freed men celebrate at the completion of the tunnel widening in the Bloomingdale area in 1893 — Contributed

- A PART OF HISTORY — Aaron Dodds, project manager for the Jefferson Soil and Water Conservation District, looks for names carved into the walls of a railroad tunnel at Bloomfield. — Linda Harris

TAKING A BREAK — Freed men celebrate at the completion of the tunnel widening in the Bloomingdale area in 1893 -- Contributed

BLOOMINGDALE — Recent efforts to clear overgrowth from Jefferson County’s Lincoln Bridge and a long-forgotten train tunnel uncovered an unexpected piece of history — a rock wall where some of the Irish, Italian and Freedmen Bureau contract workers who’d built and later widened the tunnel had carved their initials more than 140 years ago — as well as rare and diverse plants and wildlife .

Aaron Dodds, project manager for the Jefferson Soil and Water Conservation District, calls it “a rare conglomeration of historical and ecological importance that tells the story of Jefferson County, of Ohio and the nation.”

The district acquired the 370-acre tract from the state of Ohio in 2021.

“On this small section of land, George Washington, Mad Anthony Wayne and (Abraham) Lincoln have all visited,” Dodds said. “The streams flow with pristine waters and the hills are covered in old-growth forests, providing habitat for hellbenders, turtles, bobcats and Kingfishers. The property showcases monuments to the people who came before (us) and the sweat, blood and determination they poured into obtaining the American dream for themselves and building a foundation for future generations.”

So far, JSWCD has found about 50 or so names and initials on just one section of the wall and matched 17 of them to the railroad’s laborers’ ledger. At least 13 of the men whose names they’ve uncovered had at one point been with the Freedmen’s Bureau, established in 1865 to help newly freed slaves and other southerners become self-sufficient. After the bureau was abolished in 1872 many of those same former slaves found work with the railroad, which eventually hit hard times of its own and cut them loose.

A PART OF HISTORY — Aaron Dodds, project manager for the Jefferson Soil and Water Conservation District, looks for names carved into the walls of a railroad tunnel at Bloomfield. -- Linda Harris

The rest are Irishmen who came in 1847 to build the tunnel, and Italians brought in to move the creek in the late 1870s.

While there are sections of the rockface they have yet to explore, Dodds figures some names were lost to history because oil and gas workers blasted through a section of the rockwall for a pipeline before the district acquired the property three years ago. The names that are visible at any given point during the day vary, depending on how the sunlight reflects off the rockface.

“A lot of these guys were born into slavery, so initials were probably the most some of them could write of their names,” Dodds said. “The thing I find interesting is that you’ll see ‘Scanlin’ up there, he was one of the Irish workers, but then when the African Americans came here, they came back to the same rock and put their names on it.”

After poring over old records and period newspapers for clues, Dodds said he knows for sure that between Tunnel 7 (Broadacre) and Tunnel 8 (Bloomfield) alone, 86 men were killed and 400 injured during construction and widening work.

“Some were hit by trains. A lot of them were killed when workers chipping away at the stone would hit one with a void behind it and the roof would collapse on them,” he said, adding many of them were buried in unmarked graves.

“A lot of the Irish that were killed died because of collapses. When the tunnel was originally built in 1848 it was a single-track tunnel. By 1884 it was the busiest rail line in North America, a train was going through every 12 minutes. They needed to widen the tunnel but they couldn’t afford to shut it down to do it, so they brought in contract workers (who at one time had been with) the Freedmen’s Bureau. While they were in there working, trains would be zipping by. Sometimes workers would step back and they’d be hit. Other times the trains were ahead of schedule and clipped them.”

With two tracks going through the tunnel “there’s wasn’t a lot of room for workers to stand,” he said. “There was a fireman on a west-bound train who heard a clinking noise so he stuck his head out a window to look back and see what was clinking and an eastbound train was coming through at the same time and decapitated him. The reason it made the newspaper was not because the guy tragically died — it was because they got to Dennison, got his body off the train and put another fireman on and they were only two minutes behind schedule.”

Then there were guys like “Big Al,” a freed man who was mowed down by a train after a timber reinforcing the tunnel snapped. Born into slavery in Alabama in 1856, ‘Big Al’ had been liberated by the Union calvary and was a contract worker with the Freedmen’s Bureau who ended up working on the Bloomfield tunnel in Jefferson County.

“He was idolized by the other workers, he outworked and outperformed everybody,” Dodds related. “He was known to be able to swing two 9-pound hammers, one in each hand, simultaneously so he could drive the steel rods in quickly. Everybody wanted to be on his crew because they’d make more money, but they also didn’t want to be on his crew because the work he did was the most dangerous.”

When the timber snapped, “he evacuated his crew and when he was trying to leave and a train flew by and clipped him, killing him,” Dodds said.

His was one of the names carved into the tunnel wall, though it’s faint.

“The railroads built Jefferson County, but these guys were brought in here because they were expendable because of prejudices, because of race,” he said. “And as they worked in the tunnels, the trains never stopped.”

Finding their names on the wall “contextualizes everything out there,” he added. “You realize these were normal guys doing their work and putting in the time. A lot of them were killed there when they were just trying to basically live the American dream. So many times we can look at some large structure or feature and we don’t think about the labor force that went it it … I think the carvings bring it home.

“The vast majority of the African American community in Steubenville are related to tunnel workers, because right after they got done doing the tunnel work there was an economic collapse and the railroad didn’t have the finances to send them on to other projects. They cut them loose and while they were here they started doing other jobs. A lot of people can trace their roots back to the tunnel workers.”

It’s just a forgotten piece of history, he said, much like the Lincoln Bridge. It’s barely visible now but Dodds said JSWCD is planning to clear the overgrowth from the bridge, set up a parking area as well as an educational area — and eventually tie into the Great American Rail Trail — the nation’s first cross-country, multi-use mile trail between Washington, D.C., and Washington state.

The coup de grace would be a statue of Lincoln at the bridge.

Lincoln, en route to Washington, D.C., for his inauguration, had to walk across the original wooden span after a large sycamore tree dislodged by a storm crashed into and compromised the wooden trestle. When Lincoln’s train reached the trestle, fearing the bridge wouldn’t support the weight of it, he was asked to walk across. Lincoln obliged, but as he crossed the trestle he slipped on the wet, greasy wood and nearly plunged to his death.

One of his first acts as president was to have a stone bridge built to replace the wooden trestle in the name of national defense.

During World War II, some 80 percent of America’s servicemen and women traveled through the same tunnel and across the Lincoln bridge.

“The tunnel, the Lincoln Bridge, the carvings have all been sitting here for 160 years and only a handful of people have known they were here,” he said. “They’ve been sitting there, abandoned, since 1948.”

Ironically, that has a lot to do with why plant and animal species virtually extinct in other parts of Ohio are thriving on the property.

“When the railroad bypassed the tunnels in the 1950s, the property was frozen in time, which created an interesting situation where plant and animal species could thrive that had been largely pushed out of the area by development and (pollutants),” Dodds said.

Now, he said, “white trillium and ferns sprout from the tunnel faces, wild hydrangeas grow where Lincoln once stood on his way” to his inauguration. Likewise, he said the site is home to Jefferson County’s famed hellbenders, as well as other rare or endangered species.

“It’s a vital feature to preserve for conservation, education and recreation for the benefit of the people and to protect the legacy of those who made it possible,” he said. “So many old structures were demolished in the name of progress, and identity of place, along with the craftsmanship, was lost. Now, we have the ability to show that historical and ecological conservation can co-exist and capture the identity of place and promote quality of life.”